Any frequent reader of our blog knows we are fans of momentum investing. At this point, investment professionals should know that momentum historically works, that momentum is painful, and we have our own opinions on how to implement momentum investing via our Quantitative Momentum Index.

Sometimes we feel there is nothing new when it comes to momentum. However, a new momentum investing paper, “Overpriced Winners,” by Profs Kent Daniel, Alexander Klos, and Simon Rottke, is really cool and worth consideration.

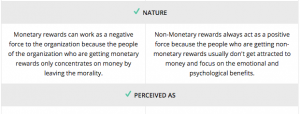

One key chart from the paper sums up everything:

The results are hypothetical results and are NOT an indicator of future results and do NOT represent returns that any investor actually attained. Indexes are unmanaged, do not reflect management or trading fees, and one cannot invest directly in an index. Additional information regarding the construction of these results is available upon request.

The chart shows that 12-2 momentum winners do well upon formation, 12-2 momentum losers do poorly (initially), and the market grinds along (we already know that).(1)But the chart also shows that “overpriced winners” are absolutely terrible.

Overpriced winners? Let’s dig in further!

What Are Overpriced Winners?

Within the high momentum portfolio (the “winners”), the authors examine a difference between what they classify as “constrained” and “unconstrained” firms. Specifically, the paper defines a “constrained” momentum firm using an independent triple sort. The authors split the universe into quintiles using the past 12_2 months returns (the stock’s momentum over the past year, ignoring the previous month). The additional two sorts are quintile ranks on (1) institutional ownership and (2) changes in short interest over the preceding year.

A “constrained” winner is a firm that is in the top quintile on 3 measures:

Behavioral finance generally theorizes that the momentum anomaly is caused by investors suffering from an underreaction to firm news / fundamentals. (underreaction) ((2) However, for this subset of high momentum firms, the authors suggest a different behavioral bias at work — unwarranted optimism.

The logic is the following, in the author’s words:

… for the constrained winners, we argue that a possible source of the price rise was that only a subset of investors revised upward their valuation of the firm in response to what we will label a “sentiment” or “disagreement” shock. For an unconstrained firm, the price would not move appreciably in response to such a shock; the subset of now-optimistic investors affected by the sentiment shock would demand more shares, but in response the arbitrageurs (whose valuation of the firm was unaffected by this shock) would short the shares demanded by the optimists. However, for a constrained stock, where it is difficult for the arbitrageurs to borrow and short the stock, competition between the optimistic investors will lead to a strong, unwarranted price rise for the stock.

No Comments