For a long time, a common assumption has been that the world will eventually “run out” of oil and other non-renewable resources. Instead, we seem to be running into surpluses and low prices. What is going on that was missed by M. King Hubbert, Harold Hotelling, and by the popular understanding of supply and demand?

The underlying assumption in these models is that scarcity would appear before the final cut off of consumption. Hubbert looked at the situation from a geologist’s point of view in the 1950s to 1980s, without an understanding of the extent to which geological availability could change with higher price and improved technology. Harold Hotelling’s work came out of the Harold Hotelling, which was concerned about running out of non-renewable resources. Those using supply and demand models have equivalent concerns–too little fossil fuel supply relative to demand, especially when environmental considerations are included.

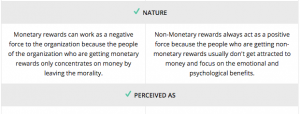

Virtually no one realizes that the economy is a self-organized networked system. There are many interconnections within the system. The real situation is that as prices rise, supply tends to rise as well, because new sources of production become available at the higher price. At the same time, demand tends to fall for a variety of reasons:

The potential mismatch between amount of supply and demand is exacerbated by the oversized role that debt plays in determining the level of commodity prices. Because the oil problem is one of diminishing returns, adding debt becomes less and less profitable over time. There is a potential for a sharp decrease in debt from a combination of defaults and planned debt reductions, leading to very much lower oil prices, and severe problems for oil producers. Financial institutions tend to be badly affected as well. If a person looks at only past history, the situation looks secure, but it really is not.

Figure 1. By Merzperson at English Wikipedia – Transferred from en.wikipedia to Commons

Substitutes aren’t really helpful; they tend to be high-priced and dependent on the use of fossil fuels, including oil. They cannot possibly operate on their own. They add to the “oversupply at high prices” problem, but don’t really fix the need for low-priced supply.

Why supply tends to rise as prices rise

For any non-renewable commodity, there are a wide variety of resources that will “sort of” work as substitutes, if the price is high enough. If the price can be raised to a very high level, the funds available will encourage the development of more advanced (and expensive) technology.

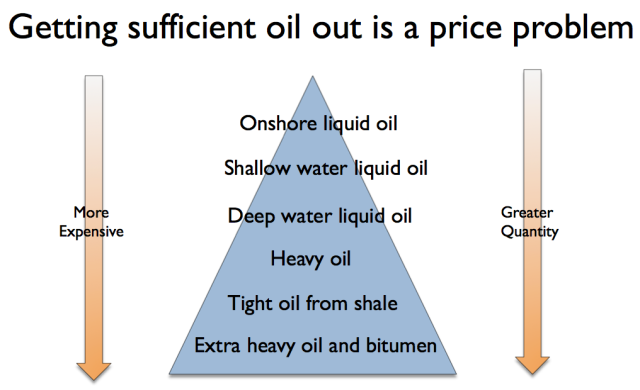

If it is possible to raise the price to a very high level, it is likely that a very large quantity of oil will be available. Figure 1 shows some of the types of oil available:

I got my idea for Figure 2 from a natural gas resource triangle by Stephen Holditch.

Figure 3. Stephen Holditch’s resource triangle for natural gas

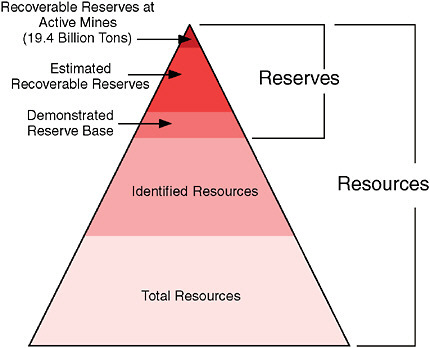

A similar resource triangle is available for coal (from National Academies Press; Coal Resource, Reserve, and Quality Assessments):

Figure 4. Coal resources in 1997, based on EIA data. Image from National Academies Press.

Because of the availability of an increasing amount of resources, we are likely to get more oil, natural gas, and coal, if prices rise. We associate high prices with scarcity; instead, high prices tend to make a larger quantity of energy product available.

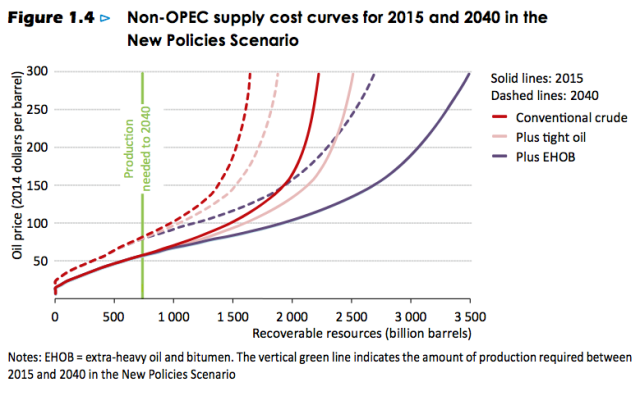

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has a different way of illustrating the likelihood of huge future oil supply, if prices can only rise high enough.

Figure 5. Figure 1.4 from International Energy Agency’s 2015 World Energy Outlook.

The implication of this chart is that the IEA believes that oil prices can rise to $300 per barrel, giving the world plenty of oil to extract for many years ahead.

Can consumers really afford very high-priced energy products?

In my view, the answer is “No!” If oil is high priced, then the many things made with oil will tend to be high priced as well. Wages don’t rise with oil prices; most of us remember this from the oil price run-up of 2003 to 2008.

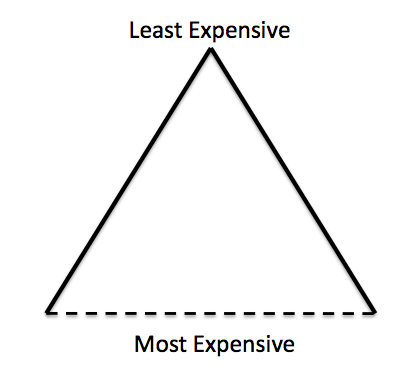

Because of this affordability issue, the limit to oil production is really an invisible price limit, represented as a dotted line. We can’t know in advance where this is, so it is easy to assume that it doesn’t exist.

Figure 6. Resource triangle, with dotted line indicating uncertain financial cut-off.

The higher cost of extraction is equivalent to diminishing returns.

As we are forced to seek out ever more expensive to extract resources, the economy is in some sense becoming less and less efficient. We are devoting more of our human labor and other resources to extracting fossil fuels, and to extracting minerals from ever-lower quality ores. In some sense, we could just as well be putting these resources into a pit and burying them–they no longer help us grow the rest of the economy. Using resources in this way leaves fewer resources to “grow” the rest of the economy. As a result, we should expect economic contraction when the cost of oil extraction rises.

In fact, economic contraction seems to happen when oil prices rise, at least for oil importing countries. Economist James Hamilton has shown that 10 out of 11 post-World War II recessions were associated with oil price spikes. A 2004 IEA report says, “. . . a sustained $10 per barrel increase in oil prices from $25 to $35 would result in the OECD as a whole losing 0.4% of GDP in the first and second years of higher prices. Inflation would rise by half a percentage point and unemployment would also increase.”

No Comments